Glasgow Cathedral

Glasgow, United Kingdom

www.glasgowcathedral.org

🇫🇷 🇬🇧

West front of Glasgow Cathedral

© Bewahrerderwerte, 2018, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This content has been published in the context of Glasgow’s 850th birthday.

Text: Andrew Ralston, The Society of Friends of Glasgow Cathedral.

Published on 12 February 2025.

The history of Glasgow Cathedral goes back to the year 612 when St. Kentigern (also known as St. Mungo) is believed to have been buried on the site. As with many medieval saints, much of the story of his life consists of legend, but it is likely that he built a church beside the Molendinar Burn (‘burn’ being a word used in Scotland for a stream or small river). This site became the centre from which Glasgow evolved. Kentigern’s sphere of influence was extensive as his bishopric stretched towards Ben Lomond in the north and down to Cumbria in England, though at that time these locations would have been part of what was known as the kingdom of Strathclyde.

The story of Glasgow Cathedral becomes clearer from the eleventh century onwards. King David I of Scotland was a strong supporter of the autonomy of the Scottish Church and it was during his reign that a new cathedral was dedicated (but probably not completed) in July 1136 under Bishop John.

At this time the Archbishop of York claimed to have authority over the Church in Scotland but by 1175 Glasgow had managed to obtain recognition of its special status from Pope Alexander III as “our special daughter, no-one in between.” King William the Lion granted to the Bishop of Glasgow and his successors “the privilege of having a Burgh at Glasgow, with a market on Thursdays, and all the liberties, and customs of the King’s Burghs.” The granting of this charter is being marked by numerous commemorative events in 2025 as part of the Glasgow 850 celebrations.

The Cathedral steadily grew in size and status thereafter. The ‘Melrose Chronicle’ records that under Bishop Jocelin, the building was “gloriously enlarged” and a second dedication took place in July 1197. It was Jocelin who commissioned a life of St. Kentigern to be written, praising his miracles and encouraging the growth of the cult of the Saint. The ambitious vision of Bishop Bondington (1233-58) was to expand to the east in order to provide a still more impressive site for the shrine of St. Kentigern. As the ground was sloping, this necessitated building the lower church which is perhaps the most distinctive architectural feature of the Cathedral as we see it today. The status of Glasgow Cathedral as a pilgrimage site can be seen from the fact that King Edward I of England made offerings in both the upper and lower churches in 1301. With the elevation of Glasgow to an archbishopric in 1492, the Cathedral became even more important.

Things changed radically after the Reformation of the 1560s. The Church of Scotland adopted a Presbyterian rather than Episcopal structure, with authority vested in a series of assemblies or courts rather than in bishops, although during the seventeenth century the Stuart kings made attempts to reintroduce episcopacy and it was not until 1690 that the Presbyterian form of the Church of Scotland was secured.

The nature of worship within the Cathedral also changed significantly. The elaborate practices of medieval Catholicism were replaced by a simplified form of worship based on the principles of sola gratia, sola fide, sola scriptura (“grace alone, faith alone, Scripture alone”). Images and side chapels with altars dedicated to saints were removed, while ritualistic services involving processions and separation of clergy in the quire from the lay congregation in the nave gave way to a new emphasis on the centrality of preaching the Word, for which such a large building was ill-suited. Hence, from the sixteenth until the early nineteenth century, ‘the Cathedral’ was not the home of one church but three. The building was divided up for the use of separate congregations: the Inner High Kirk (in the quire), the Outer High Kirk (in the nave) and the Barony (in the lower church).

It was not until the 1830s that the city of Glasgow woke up to the fact the Cathedral was a place worth preserving. The architectural unity of the building was reinstated and much restoration work undertaken, though some regret the demolition of the two western towers in the 1840s. Today it is possible to view the entire structure in all its glory.

Today, the Cathedral continues to function as an active congregation in the Reformed tradition as part of the Church of Scotland. Strictly speaking, the term ‘cathedral’ refers to the seat of a bishop but, being Presbyterian in structure, the Church of Scotland does not of course have bishops. Nevertheless, for historical reasons, the building is still known as Glasgow Cathedral.

1693 engraving of Glasgow Cathedral by John Slezer

John Slezer (d. 1717), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The two towers at the west front were demolished in the nineteenth century.

Glasgow Cathedral seen from South-East © Andrew Ralston.

The choir viewed from the pulpit

© Stinglehammer, 2017, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Three Treasures from Glasgow Cathedral

The Lower Church

Tomb of St. Mungo in the Lower Church © Andrew Ralston.

The most distinctive architectural aspect of Glasgow Cathedral is the lower church, or crypt. It is 37.5 metres in length. One historian has written that the master mason who designed it “achieved prodigies of spatial manipulation”, the aim being to place emphasis on the central area around the tomb of St. Mungo and the Lady Chapel at the east end. The ceiling was considered by architectural historian Richard Fawcett to be by far the most complex essay in vaulting to be attempted at this period in Scotland. There is a skillful variation in the design of the pillars, notably those surrounding the tomb of St. Mungo which is positioned on a raised platform within four slender pillars. When viewed externally from the rear, or from within the Necropolis, the height at the East End of the Cathedral is at its most impressive, with the combined height of lower and upper churches reaching 23 metres.

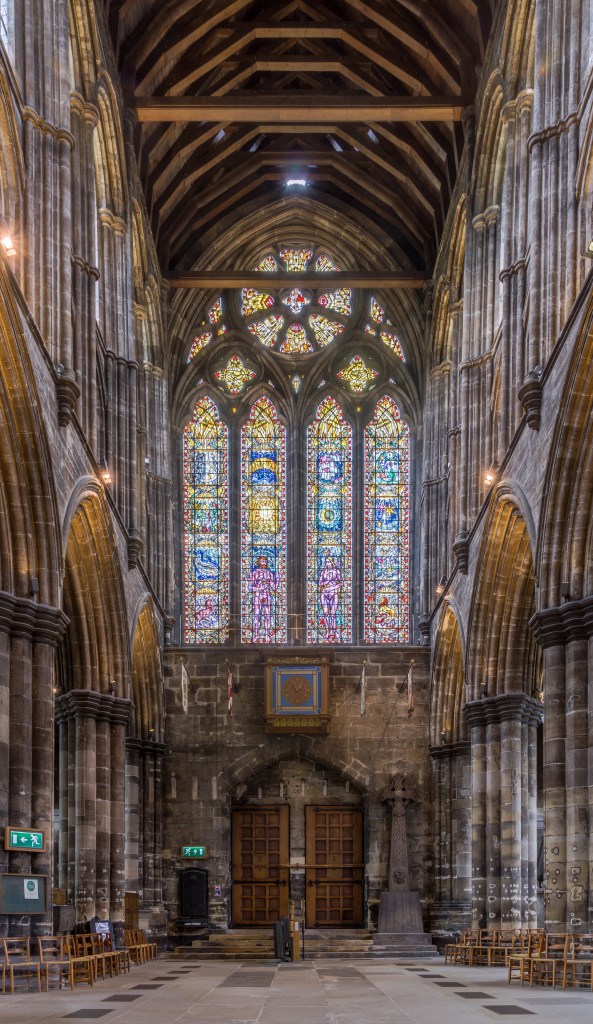

20th century stained glass windows

The Great West Window in Glasgow Cathedral by Francis Spear (1958) depicts the Creation.

© Colin, 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Eric Milner-White, Dean of York, said that the windows in Glasgow Cathedral were “the most comprehensive and representative collection of modern stained glass anywhere in Britain”. Milner-White was certainly qualified to judge, for he was a recognised authority on the subject who had overseen the replacement of windows at York Minster.

The quality of the glass in Glasgow Cathedral was largely the achievement of Rev. Dr. A. Nevile Davidson, Cathedral minister from 1935 until 1967. When Davidson came to the Cathedral the windows were mostly nineteenth century Munich glass which was in fashion when installed but had deteriorated with the passage of time, giving the interior of the building a dark, gloomy feel. By setting up a Society of Friends of the Cathedral in 1936, Davidson encouraged public bodies and individual donors to contribute to major renovation and between then and the early 1960s a huge programme of reglazing was undertaken. Sir Albert E. Richardson, formerly Professor of Architecture at London University, was appointed as adviser and leading stained glass artists of the era such as Francis Spear, Herbert Hendrie, Sadie McLellan, Gordon Webster and others were commissioned to make the windows.

Pictured here is one of the most impressive of these installations: the Great West Window above the entrance doors to the Nave. Donated by the Corporation of the City of Glasgow and made by Francis Spear in 1958, this depicts the days of the Creation. The centre lights contain the figures of Adam and Eve, flanked on either side by the creation of the fish and birds. Across the centre of the window can be seen the sun, moon and stars. From the rose window above, shafts of light emanate from a representation of the Lamb of God.

New windows have been added periodically, the most significant in recent years being a window symbolically depicting the Tree of Jesse, made by Emma Butler-Cole Aiken in 2018. This is a visual representation of the ancestry of Jesus, based on words from the prophecy of Isaiah, chapter 11: “And there shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse, and a branch shall grow out of his roots.”

The organ

The organ © Andrew Ralston.

The tradition in post-Reformation Scottish churches was to have no instrumental accompaniment, praise being led by a Precentor. During the later nineteenth century, however, there was in some circles a reaction against what was seen as the plainness and austerity of Scottish worship. Some of the larger churches, such as Glasgow Cathedral, began to adopt a more elaborate and liturgical style of worship and the installation of organs became increasingly popular.

The first permanent organ installed in the Cathedral post-Reformation dates from 1879. This was a three-manual instrument built by Henry Willis (known as ‘Father’ Willis) who was well-known for building an impressive organ for the Great Exhibition in London in 1851. The first organist at the Cathedral was Dr. Albert Lister Peace (1844-1912) who was said to have had a “wonderful power of adapting all kinds of orchestral and other music for his instrument” and an ability to make Bach sound “modern and lively” [Glasgow Herald, 15 March 1912].

As is the case with most pipe organs, the instrument has periodically been rebuilt and in 1903, 1913, 1922 and 1931 later generations of the Willis firm enlarged the organ to four manuals. Further rebuilds took place in 1971 (by J.W. Walker and Sons) and a reconstruction in 1996 (by Harrison and Harrison) returned the organ more closely to the original ideals of Father Willis.

The current Director of Music is Andrew Forbes and the Organist is Professor Malcolm Sim. The instrument can be heard every Sunday at morning worship and there are regular organ recitals.

Further Reading:

“Where Mortal and Immortal Meet” by Andrew G. Ralston (Wipf & Stock, 2021 ISBN 978-1-7252-9951-1). Essays on aspects of the history of Glasgow Cathedral by eminent historians of the past and new and hitherto unpublished research.

To order, contact: https://glasgowcathedral.org/publications.