A Taste for the Renaissance: a dialogue between collections

Al Thani Collection, Paris

6 March – 30 June 2024

www.thealthanicollection.com

🇫🇷 🇬🇧

From 6 March to 30 June 2024, The Al Thani Collection at the Hôtel de la Marine presents A Taste for the Renaissance: a dialogue between collections, the second in a series of three exhibitions held in collaboration with the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. This exhibition celebrates the extraordinary innovation and the technical virtuosity of Renaissance art, and explores its enduring appeal to collectors through the ages. For the first time since its opening, all four galleries of The Al Thani Collection will be renewed.

Presenting masterpieces from the collections of the museum alongside those of The Al Thani Collection, the exhibition highlights the complex interconnections of the Renaissance world, a golden age of exploration and discovery which witnessed an exchange of materials and ideas across both Europe and distant lands. Coupled with a revived appreciation for the ideals of antiquity and aesthetics, wealthy patrons commissioned significant works of art which have since been prized by many of history’s most notable collectors.

With more than 130 works of art on display throughout all four galleries, including some of the most renowned works from the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum, the exhibition comprises sculpture, metalwork, jewellery, glass, textiles, books, manuscripts, paintings, works on paper and exotica, many of which have never previously been shown in Paris. This includes works by Antico, Lucas Cranach the Younger, François Clouet, Vittore Crivelli, Donatello, Nicholas Hilliard, Hans Holbein the Younger and Leonardo da Vinci, together with treasures and objets d’art created for noble and royal patrons by many of the most accomplished artists of the period.

A CURATOR’S CHOICE

by Amin Jaffer,

Director of the Al Thani Collection

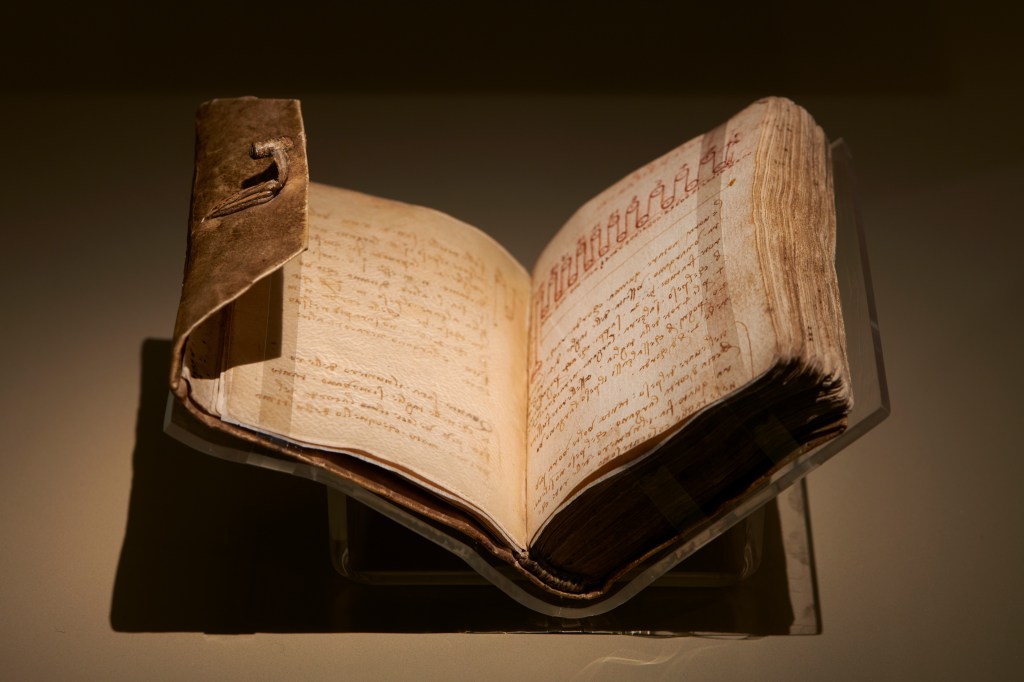

Codex Forster III

View of the exhibition « A Taste for the Renaissance: a dialogue between collections«

© The Al Thani Collection 2024. All rights reserved. Photograph Marc Domage.

Leonardo da Vinci, Codex Forster III, Milan, c. 1490-93

Pen, ink and red chalk on paper, bound in parchment. Closed: 9.3 x 7 cm.

Victoria and Albert Museum, MSL/1876/Forster/141/III, Legs de John Forster

Text: Emma Edwards, Project curator, Victoria and Albert Museum.

‘Begun in Florence in the house of Pietro di Braccio Martelli on 22 March 1508. This is a gathering of notes in no particular order, taken from numerous pages which I have copied here, in the hope that I will later place them in proper order according to the subjects they treat. And I think that before I reach the end of this, I will have repeated the same thing several times: but, reader, do not blame me, because things are numerous, and memory cannot keep them all and say « this I do not wish to write because I have already written it »‘.

Written in Leonardo da Vinci’s famous mirror script, this text is found on what is now the first page (Folio 1.r) of the Codex Arundel now in the British Library. It is one of about twenty-two notebooks that survive, alongside over 6,000 sheets of notes and drawings (some bound later, some loose) made by Leonardo during his lifetime. In his own words, this text offers profound insight into the jottings, musings, diagrams and drawings that Leonardo recorded on a vast range of subject matter, including painting, sculpture, architecture, geometry, geology, engineering, optics, anatomy, botany, hydrodynamics and astronomy; precious windows into the eclectic interests and working mind of this exceptionally talented polymath.

The Codex Forster is made up of five notebooks, bound in three small volumes that were bequeathed to the Victoria and Albert Museum by John Forster (1812-1876) in 1876. Forster, a friend of Charles Dickens, was a writer, critic and book collector. The notebooks were originally part of the collection of papers given by Leonardo to his pupil and friend, Francesco Melzi (1491/93-c.1570) and later owned by Pompeo Leoni (1533-1608), sculptor at the Spanish court of Philip II. […]

The Codex Forster III contains notes taken between 1490 and 1493, when Leonardo was in the service of Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan. Like the majority of the surviving notebooks it covers a miscellany of subjects, with notes and diagrams on geometry, weights and hydraulics, interspersed with jottings and sketches on locking devices, architecture, costumes and hats, human and animal anatomy. It also includes recipes for artistic practice, the preparation of linseed oil with mustard seed for example, and mentions books of interest, such as a « fine herbial » belonging to a certain Giuliano da Marliano.

A variety of observations often converge on a single page, alongside further notes, diagrams and rough drawings that can sometimes only be fully understood by turning them around. Much of the text is in mirror writing, from right to left. It has been suggested this was, perhaps, a way for the artist to encode or make secret the text. In reality, it may simply have been easier for Leonardo, who was left-handed, to write this way. […]

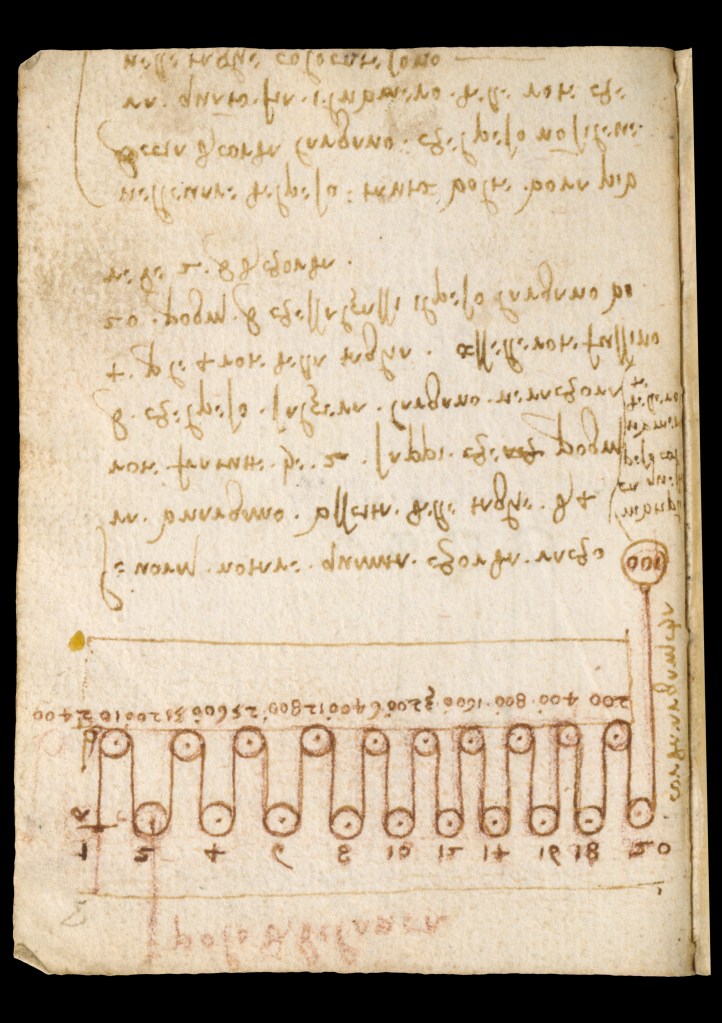

The text and diagrams on f. 86v-87r [see below] form one of several pages of notes on weights, pulleys and motion; specifically ways of quantifying lengths of rope in a twenty wheeled pulley system lifting a 100 pound weight.

Leonardo da Vinci, Codex Forster III, Milan, c. 1490-93

Pen, ink and red chalk on paper, bound in parchment. Closed: 9.3 x 7 cm.

Victoria and Albert Museum, MSL/1876/Forster/141/III, Legs de John Forster

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Antico’s Meleager

Antico (Pier Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi), Meleager, Mantua, ca 1484-90

Bronze, parcel-gilt with silver inlay, 33x18x10cm

Victoria and Albert Museum, A.27-1960

Purchased with funds from the Horn and Bryan Bequests and Art Fund support

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Text: Rachel Boyd, Senior Curator of Renaissance Sculpture, Victoria and Albert Museum.

Captured in a moment of determined action, the Greek hero Meleager balances his weight on his left leg as he strides forward in pursuit of the Calydonian boar. Artemis, goddess of the hunt, had sent the wild animal to lay waste to Meleager’s homeland because his father, King Oeneus, had neglected to honour her with suitable offerings. […]

Born in Mantua, Pier Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi (c. 1460-1528) acquired the nickname ‘Antico’ because of his careful study and imitation of ancient sculpture. He was particularly admired for statuettes such as this one, which reproduced Greek and Roman sculpture on a smaller scale. The model for Antico’s Meleager was a marble group that early viewers could admire in the Cortile del Belvedere of the Vatican and later in the Uffizi in Florence, where it was recorded by 1638. It was destroyed in a fire in 1762, but its general appearance is known through drawings. Already in the sixteenth century, however, the sculpture was in a ruined state, missing the hero’s head and limbs. Antico’s bronze was therefore not so much a reproduction as a reinvention, restoring the hero to his former glory but in even more precious materials and an entirely new context.

The even, dark surfaces of the hero’s flesh – enhanced by Antico’s application of a black patina – masterfully balance the folds of Meleager’s tunic, the curls of his hair, and the delicate laces of his sandals, all of which the sculptor enlivened with mercury gilding and then burnished to create a warm, bright tone. The eyes, in turn, are inlaid with silver, in a deliberate imitation of ancient bronzes. These finely worked surfaces and intricate details – even the hero’s individual teeth are gilded – demand to be examined at close range.

The Arundel Zodiac

The Arundel Zodiac

Intaglio: Italy, c. 1540; setting: Italy, c. 1540-50 and Netherlands (?), c. 1600-20

Cornelian, enamelled gold, diamonds, rubies / Intaglio: Diam. 4,3 cm; with setting: H. 11 ,6 cm

The Al Thani Collection, ATC1079

© The Al Thani Collection, 2021. All rights reserved.

Photography by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd.

Text: Julie Rohou, Heritage curator, Musée national de la Renaissance – Château d’Écouen.

Translated from the French by Sally Laruelle.

This remarkable jewel, exceptional in terms of both complexity and provenance, is composed of a cornelian intaglio featuring at its centre Jupiter astride his eagle, flanked by Mercury and Mars, with Neptune rising from the waves below. The composition is encircled by a frieze with the twelve signs of the zodiac. The stone is mounted in a pendant set with precious stones and enamelled gold fruits, flowers and strapwork; the reverse [see below] features a crane in basse-taille translucent enamel surrounded by flowering tendrils and a laurel wreath on a gold ground. […]

The intaglio is first mentioned in the collection of Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel (1585-1646), a passionate art collector who acquired it in 1636 from the Flemish dealer Daniel Nys (1582-1647). In 1628, the latter began to negotiate the sale of the huge collection of the Dukes of Mantua to English collectors including King Charles I, the Duke of Buckingham and Lord Arundel. It is possible that the intaglio belonged to the Mantua collection, but the imprecision of the Gonzaga inventories makes it impossible to identify it. The jewel then passed down to George Spencer, 4th Duke of Marlborough (1739-1817), who bought the Arundel collection from his sister-in-law, and it remained at Blenheim until 1899, when the collection was dispersed.

The central composition derives directly from a design by Raphael, engraved by Marcantonio Raimondi, for the frontispiece of an (unpublished) edition of the Aeneid. […]

Astrology – the study of the movements of the celestial bodies and their influence on human lives – was seen in the Renaissance as a science on a par with astronomy. It flourished at humanist courts with their passion for mystery and symbolism, and particularly at the court of Federico II Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua. Federico, who had chosen Jupiter as his emblem, commissioned several representations of the king of the gods and the mysteries of the cosmos for the Palazzo del Te in Mantua. As the Arundel Zodiac combines both themes, it may have been inspired by the erudite culture at the Gonzaga court in the 1530s and 1540s; the presence in Mantua of Giulio Romano, painter and supplier of designs, would easily explain the similarity of the intaglio to Raphael’s design.

The Arundel ZodiacIntaglio: Italy, c. 1540; setting: Italy, c. 1540-50 and Netherlands (?), c. 1600-20

Cornelian, enamelled gold, diamonds, rubies / Intaglio: Diam. 4,3 cm; with setting: H. 11 ,6 cmThe Al Thani Collection, ATC1079 © The Al Thani Collection, 2021. All rights reserved. Photography by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd.