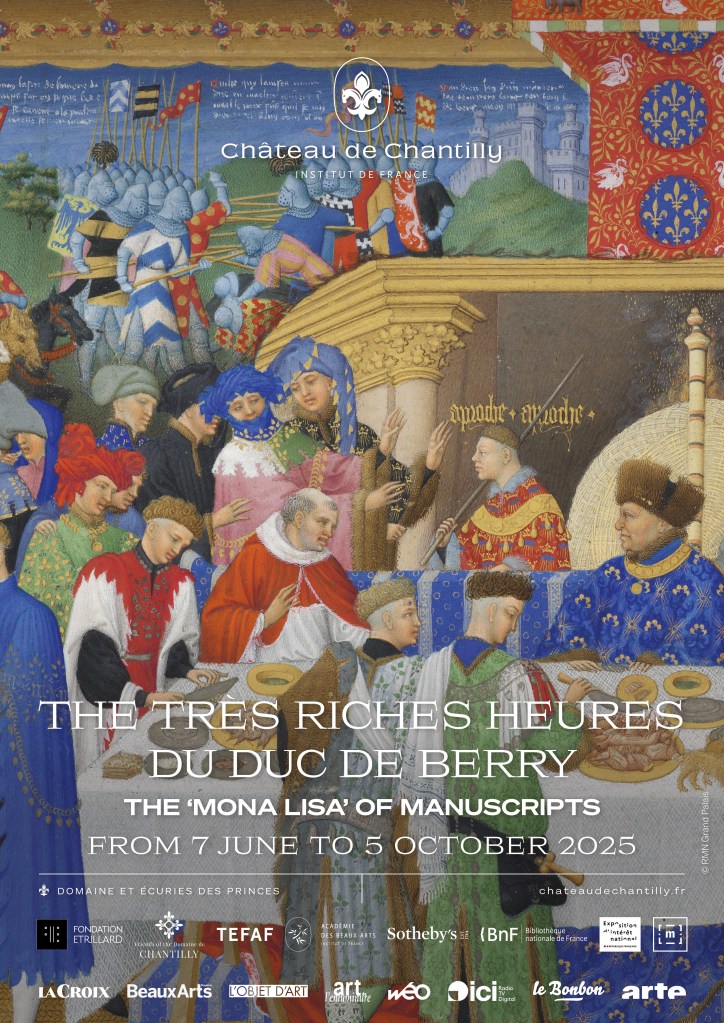

The Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry

Château de Chantilly, Chantilly

7 June – 5 October 2025

chateaudechantilly.fr

🇫🇷 🇬🇧

PRESENTATION

The Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry

The ‘Mona Lisa’ of manuscripts

[Text from the Press Kit]

A true icon of the Middle Ages, the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry is the jewel in the crown of the Musée Condé’s collections in Chantilly, France. In accordance with the wishes of its donor, the Duke of Aumale, the manuscript cannot be exhibited outside the Musée Condé where, because of its fragility and value, it is usually kept out of sight and in a safe place. Having suffered from a number of issues, the manuscript had to be restored. This restoration, preceded by months of scientific analysis and preliminary studies, means that for the first time, and probably the last, 26 pages (from the legendary calendar) can be shown at the same time. The exhibition accompanying this major event provides a context for this ‘cathedral book’ and explores its incredible influence. Around 1411, the eminent collector and bibliophile Jean, Duke of Berry commissioned three master illuminators, the Limbourg brothers, to create a book of hours for him, a work that would remain unfinished after both the duke and the illustrators died in 1416. Throughout the rest of that century, other illuminators completed the work, such as Barthélémy d’Eyck around 1446 for the French royal family, and Jean Colombe around 1485 for Charles I of Savoy, who had inherited it. Following its move to Chantilly and the first reproductions commissioned by the Duke of Aumale, the book acquired worldwide fame, giving it iconic status. It still conjures up a romantic and idealised vision of the Middle Ages in the public imagination.

In December 1855, Antonio Panizzi, an Italian political refugee and librarian at the British Museum, mentioned a book to his friend Henri d’Orléans, who was living in exile in London. At the age of 33, Prince Henri d’Orléans, Duke of Aumale, fifth son of King Louis- Philippe, already owned a famous collection of bibliophilic works. The Duke of Aumale travelled to Genoa and realised that the manuscript for sale was one of the books from the book of hours created for the Duke of Berry, a prince he knew well from the Condés manuscripts he had inherited. The minute the Duke of Aumale recognised it, he bought it for 18,000 francs, his collection thus acquiring unrivalled prestige. In addition to its artistic excellence, the manuscript has a powerful symbolic value that established Henri d’Orléans as one of the greatest book-collecting princes that the world has ever known. The prince began studying the book with eminent scholars. He noted that various painters had succeeded each other, recognised some of their Italian models, and gradually identified the castles and châteaux as he read. Taking his acquisitions in a new direction, he gathered together the greatest milestones in the history of book illumination at Chantilly, including the Heures du Duc de Berry, which he considered to be the ‘apogee’ of painting among illustrated books. It was not until the Duke of Aumale returned to France in 1871 that Léopold Delisle, administrator of the Bibliothèque Nationale and his colleague at the Institut de France, identified the manuscript in the post-death inventory of the Duke of Berry that was drawn up in 1416. This document is what gave the manuscript the name of the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, but only after the death of the Duke of Aumale.

Jean of Berry is remembered as a major bibliophile. Of the 300 or so works in his library, kept mainly at his home in Mehun-sur-Yèvre in the Berry region of France, 127 have now been identified and form the crème de la crème of libraries the world over. According to Christine de Pizan, Jean of Berry ‘loved fine books on moral and political science, Roman history and instructive reading.’ As well as the sumptuous books of hours, he had a diverse and scholarly collection, which included encyclopaedias, early humanism and contemporary authors. He also employed the services of prestigious illuminators. His library is a harmonious blend of knowledge and luxury. The Duke of Berry owned 6 psalters, 13 breviaries and 18 books of hours. He personally commissioned 6 of them: these were works of art on which the most talented illuminators worked for many years under the prince’s direction. They have all been assembled here together for the first time since the death of the Duke of Berry in 1416! The 6 bespoke books he commissioned from the greatest artists of his time form an exceptional series of works. They take their name from the terms used to describe them in 15th Century inventories. Through them, the Duke asserts his rank, shows off his personality and proves his profound devotion.

The Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry can be seen here:

les-tres-riches-heures.chateaudechantilly.fr

The Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry exhibition © Muriel Vatrin

The Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry exhibition © Muriel Vatrin

The manuscript is in the case in the middle of the room.

The Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry exhibition © Muriel Vatrin

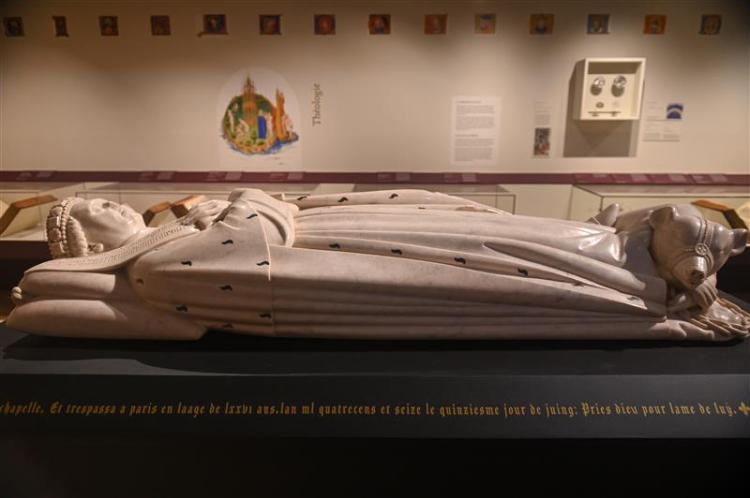

The effigy of the Duke of Berry.

A SELECTION OF TREASURES

by the curators,

Mathieu Deldicque, Chief Curator, Director of the Musée Condé

and the Living Horse Museum, Château de Chantilly,

in collaboration with Marie-Pierre Dion,

General Library Curator, Musée Condé, Château de Chantilly

Psalter of Jean de Berry

The Effigy of the Duke of Berry © Muriel Vatrin

The recumbent statue of Duke Jean de Berry was originally part of a particularly sumptuous monumental funerary ensemble installed in the choir of the Sainte-Chapelle in Bourges. The funerary monument was probably commissioned during the Duke’s lifetime, much the same as his father Charles V and his brother the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Bold had commissioned theirs. The exact date of the commission is not known, but in 1404, the Duke announced his intention of being buried in the Sainte-Chapelle. It is likely that the tomb was possibly commissioned shortly after Jean de Cambrai’s time as the Duke’s sculptor. In the meantime, Jean de Cambrai died in 1438. The King therefore paid his heirs for the recumbent effigy, which can reasonably be attributed to the great sculptor, as well as several of the mourners. The rest of the tomb, especially most of the mourners on the plinth, was sculpted by another team. After the chapel was demolished, the tomb was moved to the lower church of Bourges Cathedral, where it was vandalised and partially destroyed in 1793. The mourners were then scattered. The recumbent statue was miraculously spared, as was its black marbles lab, bearing a funerary inscription along its edge.

The Duke is shown lying down, dressed in a robe and mantle of white marble decorated with black marble ermine, his arms simply crossed over his chest. His right hand held a sceptre, destroyed at least as long ago as the 18th Century, while his left hand held a scroll. His head, encircled by an elaborate ducal crown, rests on a cushion, and his feet are resting on a sleeping bear. The practice of placing a symbolic, psychopompic animal at the feet of the deceased has been a tradition since the 13th Century. The original element here is the choice of a bear, which is both symbolic of the Duke and a reference to the patron saint of Berry, Ursin.

The tomb of the Duke of Berry suffered the same fate as the Très Riches Heures: an extraordinarily ambitious and unusual project, left unfinished at the death of its patron in 1416. It was initiated by an exceptional artist, who came from the North of France like the Limbourg brothers and, like them, enjoyed a special place in the ducal entourage.

Virgin and Child with Butterflies

Virgin and Child with Butterflies, Jean Malouel, circa 1410-1415

© BKP Berlin Distribution Grand Palais Rmn – Jörg P. Anders

‘Item, en une layette plusieurs cayers d’unes très riches heures que faisoient Pol & ses frères, très richement historiez & enluminez. – 500 livres.’ [Item, in a layette, several volumes of a very richly illustrated book made by Pol and his brothers, very richly illustrated and illuminated.] This mention of the Très Riches Heures in the post-death inventory of Jean of Berry in 1416 made it possible to attribute this work to three illuminator brothers, Herman, Paul, and Jean de Limbourg. Originally from Nijmegen, capital of the Duchy of Guelders (now the Netherlands), they arrived in France in the wake of their uncle Jean Malouel, who himself worked for the queen of France before becoming painter to the Duke of Burgundy. Two of them also trained as goldsmiths in Paris. Taken hostage in Brussels on their way to Nijmegen, they were freed by the Duke of Burgundy and entered his service. The latter’s death in 1404 signalled a change in patronage, and they were employed by his brother, Jean of Berry. Benefiting from a special place in the prince’s entourage (Paul was the duke’s painter), they created some of the most revolutionary illuminated works of the late Middle Ages.

This painting is one of the few that can be attributed to Jean Malouel. The cascading drapery of the Virgin’s mantle, sculptural and plastic in quality, can also be seen in the works of the Limbourg brothers. The butterflies may symbolise the soul and resurrection, or refer to heraldic elements, or even to flying flowers. The Limbourg brothers’ masterpiece, the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, displays a multitude of inspirations, ancient and modern, Nordic, Germanic, Eastern and Italian, combined with the grand tradition of fine book illumination in the 14th Century. The Limbourg brothers learnt a lot from certain Italian paintings in the collections of French princes or the court of Avignon, in particular those by Simone Martini of Siena and his entourage, and a number of Florentine frescoes. Drawings and manuscripts were easily transported, giving the Limbourgs access to the latest developments in Italy. They, in turn, inspired artists in that country too.

The Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry

(the month of September)

September

Extract from the Calendar of the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry

Paris and Bourges, 1411-1485

© RMN-Grand Palais / Domaine de Chantilly / Michel Urtado

The Très Riches Heures was lost after the death of the Duke of Berry and the Limbourg brothers in 1416. Left unfinished, it probably remained in Paris, perhaps with a merchant charged with liquidating the prince’s debts. We next pick up the trail after the Recovery of Paris by Charles VII in April 1436. Jean Haincelin (the Dunois Master), son of Haincelin de Haguenau (the Bedford Master), must have knowledge of it, as he extensively evoked the Très Riches Heures in his own works. So did the manuscript then enter the collections of Charles VII? We know that in 1446, Barthélemy d’Eyck, painter to King René, brought with him the latest developments in Flemish painting. Under the Château de Saumur, depicted in the calendar for the month of September, the illuminator memorialises the lists at the Pas d’armes de Saumur, a grand forty-day tournament held in June 1446 by King René in honour of Charles VII. Thus, this second decoration campaign in 1446 had been launched very swiftly.

At the end of the 15th Century, the Très Riches Heures entered the library of the Dukes of Savoy. The Bourges illuminator Jean Colombe was paid in 1485 by Charles I of Savoy to complete the decoration of the manuscript. Colombe was protected by Queen Charlotte of Savoy, wife of King Louis XI and aunt of Charles I, Duke of Savoy. It is not certain whether the Très Riches Heures was passed on to him by the queen; there were other possible channels (the mother of Charles I, Duke of Savoy, Yolande of France, was King Charles VII’s daughter, for example). Influenced by the miniatures of the Limbourg brothers and Barthélemy d’Eyck, Jean Colombe took a number of sketchbooks back with him to Bourges, and these were to have a lasting impact on the style of illumination in the Berry region, making it the main source of inspiration for this masterpiece.

The Très Riches Heures remained in the collections of the Dukes of Savoy until Philibert II, husband of Marguerite of Austria. After the death of her husband in 1504, Charles V’s aunt was forced to leave Savoy in 1506 to assume the regency of the Netherlands. She took the Très Riches Heures with her to Malines, where it was finally bound! The manuscript inspired the artists of her court, with Simon Bening at the forefront. After Margaret of Austria’s death in 1530, the manuscript was passed to her Treasurer General of Finances. It then travelled to Genoa, probably in the belongings of Ambrogio Spinola, commander-in-chief of the Spanish forces, and remained in Genoa until 1856, when it was acquired by Henri d’Orléans, Duke of Aumale, the founder of the Musée Condé.

PRACTICAL INFORMATIONS FOR VISITORS

What?

The Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry. The ‘Mona Lisa’ of manuscripts.

The exhibition is organised by the Musée Condé (Château de Chantilly). It benefits from the exceptional partnership of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and the Musée du Berry in Bourges. It has been awarded the “Exhibition of National Interest” label by the French Ministry of Culture

Curatorship : Mathieu Deldicque, Chief Curator, Director of the Musée Condé and the Living Horse Museum, Château de Chantilly, in collaboration with Marie-Pierre Dion, General Library Curator, Musée Condé, Château de Chantilly

Where?

Château de Chantilly (Musée Condé / Salle du Jeu de Paume)

Rue du Connétable

60500 Chantilly

chateaudechantilly.fr

When?

From 7 June to 5 October 2025

Everyday, except on Tuesdays, from 10am to 6 pm.

How much?

Ticket exhibition + park: full price 12 euros / reduced price 10 euros.

Ticket exhibition + park + château + Great Stables + temporary exhibitions and equestrian animations: full price 21 euros / reduced price 17,50 euros.