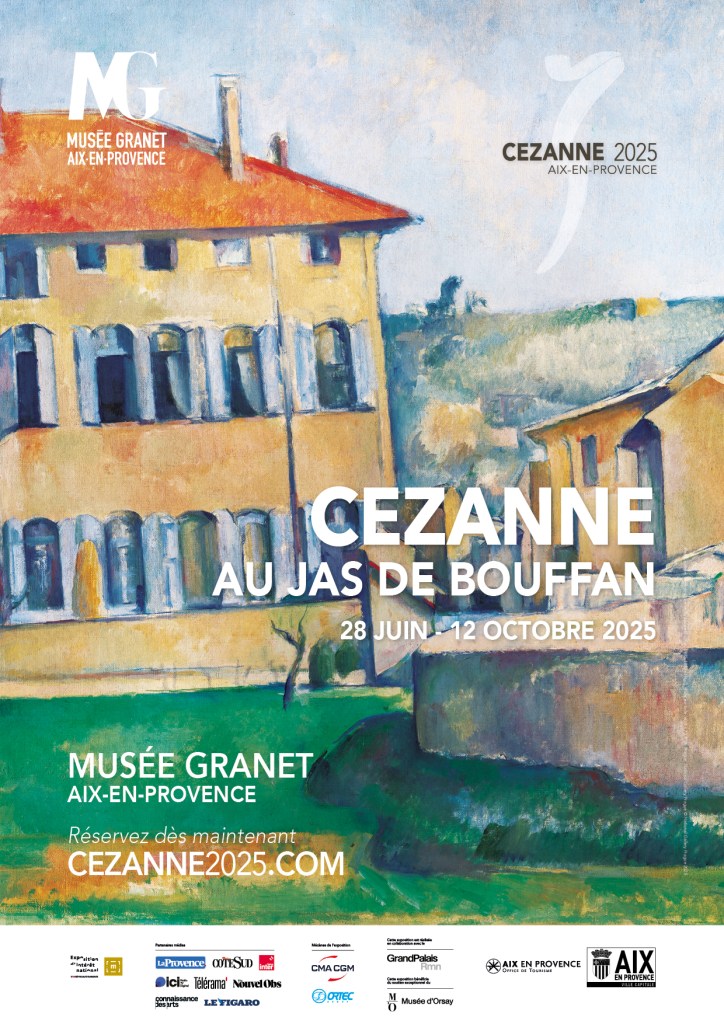

Cezanne at Jas de Bouffan

Musée Granet, Aix-en-Provence

28 June – 12 October 2025

www.museegranet-aixenprovence.fr

🇫🇷 🇬🇧

PRÉSENTATION

Cezanne at Jas de Bouffan

[From the Press Kit]

June 2025 marks the start of a cultural season in Aix-en-Provence, celebrating the life and work of its native son, Paul Cezanne, and the landscapes and mountain made famous through his paintings, and which served as the backdrop to his life. Although Cezanne divided his time between his hometown and Paris, he never failed to return to Aix-en-Provence, drawn by the unique light of its countryside and his emotional connection to his birthplace. As part of its preparations for Cezanne 2025, the City of Aix-en- Provence has begun the phased restoration of Jas de Bouffan, the country house or ‘bastide’ bought by the artist’s father in 1859, part of which will be open to the public. Situated on the western outskirts of the city centre, the bastide was more than a family home to Cezanne, who was forced to sell the property in 1899. It was also where, at the age of 20, he produced his earliest paintings, some of which were recently found in the ‘Grand Salon’, and where his father set up a studio for him on the second floor, lit by a large skylight, where he painted his most celebrated masterpieces. He spent four decades in his family home, surrounded by fifteen hectares of vineyards and orchards, and it was here that he produced his still lifes, paintings of card players and bathers, portraits and self-portraits, many of which will be featured in a major exhibition at the Musée Granet from 28th June to 12th October 2025. More than 130 works, including oils on canvas, drawings and watercolours, will explore the connection between the artist and his restored family home, which is still set in nearly five hectares of virtually unaltered parkland. These priceless works have been loaned from collections around the world, including the Musée d’Orsay and The Petit Palais in Paris and museums in Basel, Chicago, Cambridge, London, Los Angeles, New York, Ottawa, Tokyo and Zurich. Visitors can start their tour in the artist’s restored family home and its gardens and even stand where he painted some of his works. They can then move on to the galleries of the Musée Granet to admire many of the pieces he produced at Jas de Bouffan. Their subjects include the house’s ‘residents’, the estate, the chestnut tree-lined avenue, the pond, and the bastide and its adjoining farmhouse, which both feature in an outstanding painting loaned by the National Gallery Prague, offering a remarkably cohesive artistic and academic picture of the artist’s work. The farmhouse adjacent to the bastide will also welcome the team responsible for the artist’s Catalogue Raisonné, in the Cezanne Research and Documentation Center, the world’s only institution with the authority to authenticate works by Cezanne.

Forced to sell the Jas de Bouffan estate in 1899, Cezanne settled in the town hall district, on rue Boulegon, before acquiring a plot of land on Lauves hill, overlooking Aix Cathedral. Here, he built a studio where, from 1902, he produced his final paintings and completed his Large Bathers, now on display at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, which he began at Jas de Bouffan. In 2016, the City of Aix-en-Provence purchased an adjoining plot to improve access to the site. This space, devoted to the artist and his studio, which has been left as it was, and his restored possessions will be among the lasting legacies of Cezanne 2025. As part of its programme of cultural events, the city also plans to open a new public trail leading to Bibémus quarry. This site, east of the city towards Mont Sainte-Victoire and intimately connected to the artist, allows visitors to walk in his footsteps and discover how the quarry profoundly influenced his work from the 1890s. The geometric landscapes he produced here marked the start of his journey to becoming the “father of Modern art” and, for artists, “father to us all”, as he was described by Picasso, whose tomb lies just a few miles away. Art and history museums in Aix-en-Provence will also run an ambitious programme of events throughout Cezanne 2025, placing the artist in his historical context and offering fresh insight into his legacy — one that was not immediately recognised in his native city or the rest of France.

A SELECTION OF WORKS OF ART

by the curators of the exhibition

Bruno Ely, Head Curator and Director, musée Granet,

and Denis Coutagne, President of the Paul Cezanne Society, former Director of the musée Granet

The Jas de Bouffan

Paul Cezanne, House and Farm at Jas de Bouffan, 1885-1887

Oil on canvas, 60,8 x 73,8 cm

Czech Republic, Prague, National Gallery Prague

© National Gallery Prague 2025

In the 1880s, Cezanne decided to explore the grounds of the bastide even further. At the time, it was set on an estate of around fifteen hectares. Jas de Bouffan is characteristic of a Provençal bastide, which had its heyday between the 17th and 18th centuries. The space is walled off. A pathway lined with chestnut trees leads up to an austere-looking mansion house. The facade of the building has windows on several levels. Water was essential on these estates to supply both ornamental gardens and farmland. To the west, Cezanne made the most of the ornamental pond motif with its dolphin and sculpted lions gushing water. To the east, he has concentrated on the farm. To the south, the artist has focused on the large trees in the grounds. And finally, beyond the walls of Jas, further east, The Sainte-Victoire mountain rises up in the distance. A mountain that would become a key and recurrent motif in his work. Cezanne gives us a monumental vision of the bastide du Jas de Bouffan. It rises up majestically in the north of the estate. However, while the artist remained relatively faithful to the motif, he has taken some artistic liberties by distorting the dimensions and perspectives. When he painted this view of the bastide in the 1880s, Cezanne had reached a period of maturity. He abandoned the colourful Impressionist-style brushwork in favour of coloured planes. Laid out on the surface of the canvas and juxtaposed one next to the other, these planes structure the pictorial space. Cezanne’s famous colour-palette developed into the sparkling blues, greyish greens, and ochres you can see here. Although these colours are saturated, the coloured layer is lighter, becoming fluid and transparent so you can almost see the canvas underneath. The house, set off-centre to give it the same importance as the farm, is leaning slightly to the left. Cezanne created this tilting movement thanks to a skilful use of false vertical and horizontal lines, which forced him to rethink the equilibrium of his composition. Ultimately, this instability enabled him to achieve an overall impression of balance.

Bathers

Paul Cezanne, Bathers, 1899–1904

Oil on canvas, 51,3 x 61,7 cm

USA, Chicago (IL), The Art Institute of Chicago, Amy McCormick Memorial Collection

© Art Institute of Chicago, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / image The Art Institute of Chicago

Paul Cezanne made the first paintings of Bathers in the 1870s. He returned to this theme in the last fifteen years of his life. They reflect his ambition of integrating the nude in movement into an open-air landscape. Here, Cezanne’s figures are reclining at the water’s edge, in a lush green setting. The artist has focused on their virile bodies. Often heavy-looking and at times ill-proportioned, these bodies boldly structure the pictorial space. We are a long way from the eroticism traditionally associated with this academic theme. The nudes have become a pretext for combining forms. The figures don’t appear to have been painted from models but taken from Cezanne’s earlier drawings. Cezanne also reveals here the influence of Nicolas Poussin’s landscapes on his work. This can be seen in the river motif that separates the foreground from the background; the staggering of the coloured planes of the landscape and the way the figures are grouped together like an ancient bas-relief. Cezanne’s intention: to blend the principles of classicism with the modern practice of working outside in the open air. As he said himself, he wanted to create, “Poussin in nature”. He succeeded in bringing together men, women and landscape in the same pictorial fabric. Made up of a multitude of colourful, hatched brushstrokes, his colour palette became radically lighter. It was now filled with shades of blues and pale greens, fleshy tones and light ochres. Cezanne skilfully harmonised these warm and cold hues. How? By pairing complementary colours. The shades echo each other. The bodies are painted with touches of colour borrowed from the vegetation and the sky. The sky mirrors the hues of the water and the trees. The trees echo the nuances of the bodies and the sky. In short, a synthesis takes place between the human figures and the landscape. Although the painter has used dark black or blue “outlines” to give substance to his bodies, emphasising these contours was impossible, because for Cezanne, it was the light that delimited objects. The quivering, directional but delicate brushwork leaves glimpses of the white canvas in places. For fear of spoiling the overall harmony of the composition, Cezanne has left the canvas blank here and there, transforming absence into a creative gesture. This is why this work is so fundamentally revolutionary.

The Card Players

Paul Cezanne, The Card Players, 1893-1896

Oil on canvas, 47 x 56,5 cm

France, Paris, musée d’Orsay, Isaac de Camondo bequest, 1911

© GrandPalaisRmn (musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

Between 1890 and 1896, Cezanne made five versions of The Card Players at Jas de Bouffan. This theme became popular in the 17th century but was rare in the work of 19th-century painters. In Cezanne’s work, it took on an unexpected solemnity. His inspiration could have come from the painting by Mathieu Le Nain, with its chiaroscuro technique. Cezanne may have seen it as a young man, at the Musée Granet. Over time, the size of his works on this theme became smaller. The composition pared down to just a minimum. And so, the painting from the Musée d’Orsay is not only the smallest, but also the most accomplished in terms of his quest for the essential. The table is the only decorative element here. The harmonious shades of blue, green, brown and ochre create an ensemble composed of coloured panels, framed by the brown woodwork. There seems to be an opening in the background. Does it open out onto some kind of walled garden? Now, let’s look at the characters. The two players are captured in a dramatic face-off. They are sitting opposite each other, on either side of a bottle which marks the median line of the painting. The rigorous framing is staggeringly simple: two men in profile facing each other, concentrating on their game of cards. Cezanne uses their solid silhouettes to ensure the equilibrium of the composition. One is dark. The other, on the right, is bright. With his arched back and floppy hat, this player is rather “rounded”. He counterbalances the stiffness of the man with the pipe, his hat and the back of his chair. Although the composition is slightly decentred to the right, the two players take up the same amount of pictorial space. Like two parentheses, the curved backs echo each other whilst the lines of their bent arms converge symmetrically towards the centre of the canvas. Their battle is implacable and silent, echoing the painter’s personal struggle with his work. Only he can reconcile them. The future of painting depends on it.