Jean-Baptiste Greuze. Childhood Illuminated.

Petit Palais, Paris

16 September 2025 – 25 January 2026

www.petitpalais.paris.fr

🇫🇷 🇬🇧

PRESENTATION

Jean-Baptiste Greuze. Childhood Illuminated.

[From the Press Kit]

The Petit Palais pays tribute to Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725 – 1805) on the occasion of the 300th anniversary of his birth. A painter of the soul, famous for his portraits and genre scenes, Greuze was one of the most important and daring figures of the 18th century. Although little known today, in his time, he was acclaimed by the public, courted by collectors, and adored by critics, Diderot in particular. The painter however, was also an utterly unique artist. A rebellious spirit, he never ceased to reaffirm his creative freedom and the possibility of rethinking painting outside of conventions.

Rarely has a painter depicted children as much as Greuze, in the form of portraits, expressive faces, or in genre scenes: at turns candid or naughty, mischievous or sulking, in love or cruel, focused or pensive, adrift in the world of adults, loved, ignored, punished, embraced, or abandoned. Like a recurring motif, they are everywhere, at times asleep in a mother’s arms, at times lost in a melancholic reverie, or occasionally seized by the fear of an event beyond their control. This exhibition highlights them in seven different sections, from early childhood to the beginnings of adulthood. The centrality of the theme of childhood in Greuze’s painting can be said to reflect the key issues of the 18th century. The new status of childhood—now considered an age in its own right—the debates over breastfeeding versus the use of wet nurses, the child’s place within the family, the importance of education in forging their personality, and the responsibility of the parents in their development were the concerns of educators and philosophers like Rousseau, Condorcet, and Diderot. These questions were on everyone’s lips. Influenced by the ideals of the Enlightenment, Greuze, through his brush and pencil, became their witness, interpreter, and even ardent defender.

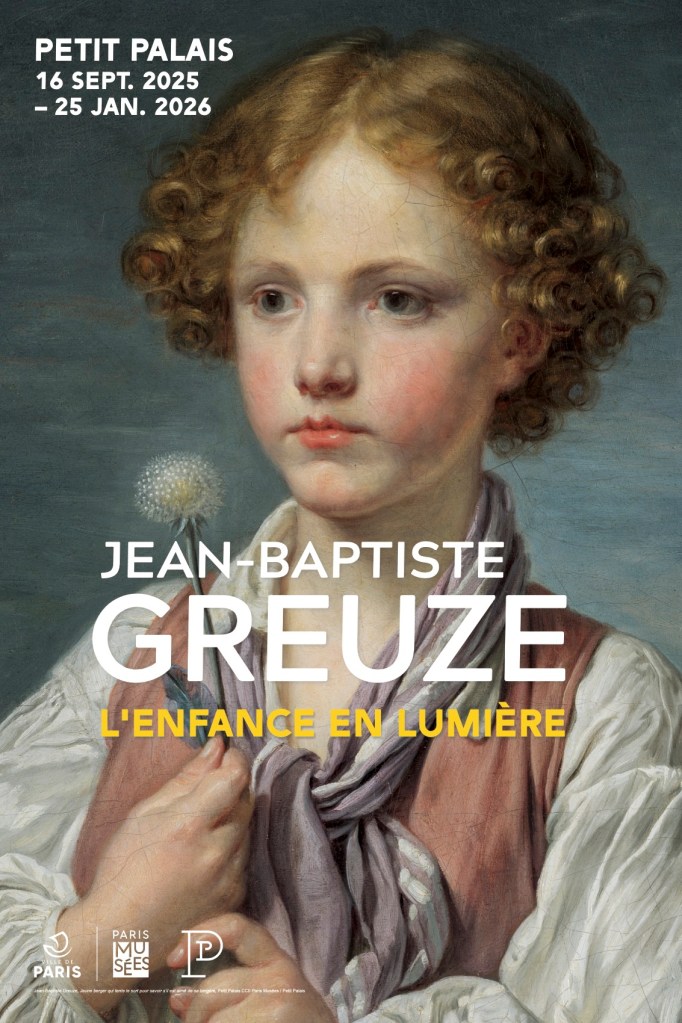

Throughout his career, the artist explored the intimacy of the family, with empathy, sometimes with humour, often with a critical dimension. He enjoyed depicting the symbolic moments or rituals that punctuate family life, such as The Giving of the Dowry (Petit Palais), The Kings’ Cake (Musée Fabre, Montpellier), and The Bible Reading (Musée du Louvre, Paris). But the domestic space was not always just a haven of peace. It was also, and often for Greuze, the scene of family disorder, the place of physical and psychological violence. Like life itself, beginning with that of the painter, which proved to be a succession of domestic misfortunes, complexity reigns in the families depicted by Greuze: the miserly father and the much maligned son, the loving father and the ungrateful son, the strict mother and the beloved child, the protective brother and the jealous sister… Greuze, radically, dared to show the tragedy of death, which children also experienced. He questioned the transition into adulthood, the loss of innocence, the awakening to love, without disguising the appetites that the beauty of the flesh could arouse in lustful old men or young predators. Faced with this adult world, often cruel, petty, and mean, we see in Greuze’s production a desire to return to the bosom of childhood, a time of purity and candour that is fragile, mysterious, and ephemeral, like the dandelion flower on which the Young Shepherd from the Petit Palais’ Collection blows in order to know if his beloved feels the same way about him.

By drawing on the threads of childhood, but in light of the great debates that animated 18th-century Paris, with its political aspirations and dreams of transformation, the exhibition reveals a work of an unexpected originality and audacity, through some one hundred paintings, on loan from some of the most important French and international collections, including the Musée du Louvre (Paris), Musée Fabre (Montpellier), Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), Rijksmuseum (Amsterdam), Kimbell Museum of Art (Fort Worth), National Galleries of Scotland (Edinburgh), the Royal Collection (Britain), as well as numerous private collections.

A SELECTION OF WORKS OF ART

buy the curators

Annick Lemoine, Chief Heritage Curator and Director of the Petit Palais,

Yuriko Jackall, Department Head of European Art

and the Elizabeth and Allan Shelden Curator of European Painting, Detroit Institute of Arts,

and Mickaël Szanto, Associate Professor, Sorbonne Université

Louise-Gabrielle Greuze

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, A young child playing with a dog

(portrait of Louise-Gabrielle Greuze), 1767.

Oil on canvas, 62,9 × 52,7 cm.

Private collection (UK) © Private collection.

To an unprecedented degree, Greuze inflected his work with elements drawn directly from his personal life. At the Salon exhibitions of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, a key event in the contemporary Parisian art scene, the painter presented portraits of his close friends, as well as paintings of his wife, Anne-Gabrielle Babuty, whom he married in 1759, his father-in-law, François-Joachim Babuty, a wealthy bookseller on the rue Saint-Jacques, and his daughters Anne-Geneviève (known as Caroline) and Louise-Gabrielle. He even portrayed the beloved family pet, a small spaniel—one of the most fashionable breeds of the period—in the arms of his daughter. To his marriage contract, dated 31 January 1759, the painter appended his elegant, imperious signature, in cursive lines, alongside that of his wife. Renowned for her beauty, Madame Greuze became his muse and model. The endearing faces of his daughters, rendered with a delicate touch, translate a father’s tenderness for his children. Greuze was an accomplished artist both publicly and privately, but he was also notoriously strong-willed and extremely slow to compromise. If we are to believe the testimony of his contemporaries, his wife had a character as strong, if not stronger, than his own. The famous chronicler of Parisian life Gabriel de Saint-Aubin Gabriel identified this painting as representing Louis-Gabrielle, Greuze’s youngest daughter. She is shown at the age of three years old in a nightdress and sleeping cap. The little dog who wriggles vigorously in her arms may be the same as the one who cuddles with Madame Greuze in the large drawing from the Rijksmuseum (see here). When it was shown at the Salon of 1769, this painting met with astonishing success; one contemporary described it as “the most universally applauded” painting in the exhibition.

The Ungrateful Son

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Father’s Curse: The Ungrateful Son, 1777.

Oil on canvas, 130 × 162 cm.

Paris, musée du Louvre.

© GrandPalaisRmn (musée du Louvre) / Photo Michel Urtado

The figure of the father, as a counterpoint to that of the child, was also central to Greuze’s work. It is precisely around the paternal image that the painter created his most ambitious compositions, whether theatrical or tragic. The father, although he was the figure of authority in the eighteenth century, was most often depicted in Greuze’s work as weakened, sick, bedridden, even deceased. Representing this period of decline interested Greuze because it allowed him to use all the tropes of pathos to translate the sublime into painting, in other words, the highest form of expression in the order of Beauty. However, in these moving scenes, in which horror combines with terror, the painter invites viewers to reflect on the role of the father in maintaining the harmony of the family. Greuze also holds the father accountable for familial imbalances, even its destruction. If the father, surrounded by his children and grandchildren, is depicted as virtuous in works such as Filial Piety (Saint Petersburg, Hermitage Museum, see here), he is shown as the opposite in paintings such as Septimius Severus and Caracalla (Paris, Musée du Louvre, see here). Here we see a malignant father who, through his neglect, has produced a monstrous son.

In the counterpart to The Ungrateful Son and The Punished Son (Paris, Musée du Louvre, see here), the father appears to be the victim of the son’s contempt, but the fury expressed on his face at his son’s unacceptable departure invites one to wonder if he himself does not bear some responsibility for his son’s shortcomings. Conceived as early as 1765, the ambitious pendants The Ungrateful Son and The Punished Son were completed over twelve years later, around 1777-1778. They illustrate in two episodes the strong tensions that tear a family apart. The first canvas depicts the eldest son, a modern image of the prodigal son, who abandons his family to enlist in the army. His father curses him, while the entire family expresses distress at his tragic departure. The power of the scene, akin to a play, is particularly striking.

The Broken Pitcher

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Broken Pitcher, 1771-1772.

Oil on canvas, 109 × 87 cm.

Paris, musée du Louvre.

© GrandPalaisRmn (musée du Louvre) / Photo Angèle Dequier

Greuze’s depictions of girls in the bloom of adolescence are undoubtedly his most technically skilful creations. This may be seen in the refined interplay of textures — satin, gauze, porcelain skin — and colours — white, cream, pale pink — in Girl with a Dove (Douai, musée de la Chartreuse, see here) or The Broken Pitcher. But while the radiant girl with the white dove appears serene —she is an allegory of innocence and purity —, The Broken Pitcher hides a dramatic reality. Throughout his career, the painter explored the transition to adulthood, that time of innocence marked by the first stirrings of love. Equally, he explored the threats to that innocence posed by predators, whether youthful seducers or lustful old men. The young girl with the broken pitcher, who has just been abused, appears frozen, her hands clenched as she attempts in vain to hold on to the flowers that she has already metaphorically lost. Her beauty reflects the purity of her soul, but her gaze, disturbing in its fixity, is definitively elsewhere, like her broken jug forever emptied of its pure water. In eighteenth-century Paris, at least in the spheres of the moneyed classes, the art world, and great lords, Greuze invited his public to see what was generally more convenient to ignore.

A young girl stares at the viewer, her dress in disarray, its ribbon untied. A cracked jug hangs from her arm. The girl’s partial nudity, her blank stare, and her disheveled attire suggest a brutal scene, likely the result of a rape. The cold grey hues echo the suggested tragedy. The girl standing at the center of this composition holds in her right arm the broken jug that gives this famous painting its name. As with dead birds or broken eggs, broken jugs symbolized the loss of virginity in the eighteenth century. The composition provides other hints as to what has transpired. On the girl’s left, on the fountain from which she had gone to draw water is a lion’s head with masculine features, while the fountain itself may be a phallic symbol. As for the girl, she clutches her dress uncertainly and her expression seems hesitant, even stunned. Breaking with tradition, Greuze was the first painter to associate the loss of virginity with the notion of trauma.